Austro-Americana Line

By Hannes Richter

From the first Austrian settlers in Georgia to the big immigration waves in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the dominant method of transportation was the ocean-going ship. The steam engine in particular, as well as subsequent development of ever bigger ocean liners, turned out to be quintessential enablers of European and Austrian emigration in significant numbers.

Today these ships have become sometimes mythical and sentimental statements of a bygone era that encompasses images that range from noble ballrooms at sea, crowded quarters for the less affluent, to the tragedy of the Titanic. Many of these big liners in transatlantic service were operated by British, German or Dutch companies, and over the years they carried millions of European emigrants to the United States and Canada, among them many Austrians. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, an Austrian shipping company joined the bee-line from Europe to America and back.

Regular transatlantic service between England and the United States began in 1840 after a mail contract was awarded to a consortium centered on Samuel Cunard, founder of the Cunard Line. Their first ship, the Britannia, sailed from Liverpool to Boston via Halifax, Samuel Cunard’s chosen home town. Cunard Steamships Limited would eventually become the major player on the European-American route and along the way it acquired several competitors, among them the White Star Line (which owned the Titanic). In 1845, the United States Congress, unhappy with a British firm dominating the transatlantic trade route, initiated state-subsidized competition, resulting in the Collins Line (officially the New York & Liverpool United States’ Mail Steamship Company), a rival to Cunard in transatlantic trade and passenger service.

Four new ships, the Atlantic, Arctic, Baltic and Pacific were built for the Collins Line by famed naval designer George Steers; at the time those vessels were not only about twice the size of Cunard’s largest ships, but could also run faster at speeds reaching twelve knots.

On her maiden voyage from New York to Liverpool, the Atlantic made the crossing in 10 days and 16 hours, half a day quicker than the previous record held by Cunard. These ships also boasted additional, new features to increase passenger comfort, including steam-heating, running water, as well as bathroom cabins or a hairdressing saloon. Despite having ships superior to Cunard’s in speed and comfort, the company went bankrupt in 1858. It was during these competitive times on the Atlantic, when European emigration to the United States began to swell. The sheer number of passengers soon presented formidable new business avenues for the ships’ operators. Service was also provided from the Netherlands (Holland America Line) and Germany (Hamburg-America Line, which at times was the world’s largest shipping company). The bulk of transatlantic traffic was handled by those big carriers, and a large number of emigrants from the Habsburg Empire utilized their services until an Austrian player entered the transatlantic shipping game

Austro-Americana

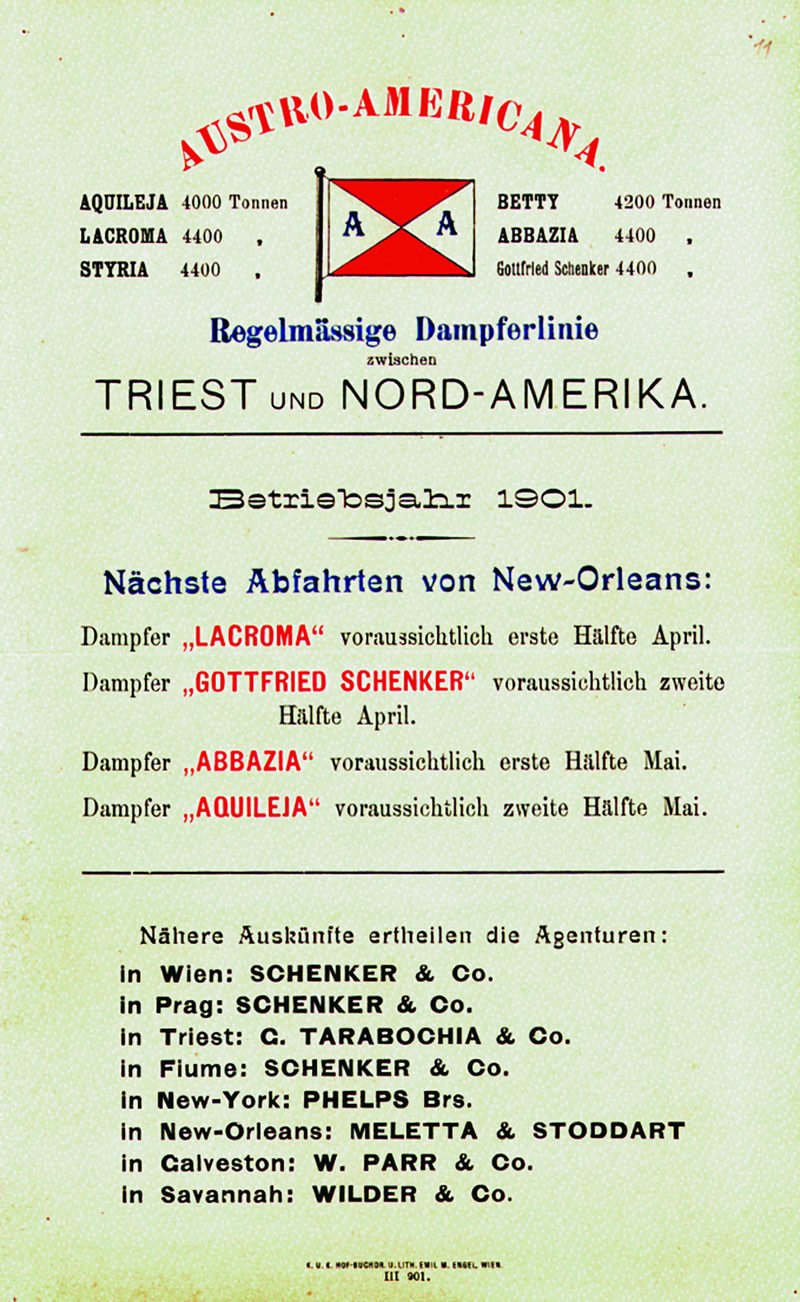

Austro-Americana was an Austrian shipping company founded in 1895 by the Austrian hauler Gottfried August Schenker and Scottish shipping merchant William Burell to establish a freight line between Austria and North America, initially with an eye on supplying the Austrian textile and cotton industry. The company was headquartered in the port city of Trieste, Italy, then ruled by Austria-Hungary. It was also known as Unione Austriaca di Navigazione, Unione Austriacaand later as the Cosulich Line, but is most commonly referred to as Austro-Americana. At first it operated four ships acquired in England, mostly to and from the ports of Mobile, Brunswick, Charleston, Wilmington and Newport News. Additional routes eventually also served South America and New Orleans, as well as other ports based on demand.

Business was good and between 1897 and 1898 a total of seven additional used ships were bought to cope with demand until the economic crisis in 1901 and 1902 forced the company to sell some of the vessels again. In 1902 co-founder William Burell left the company and sold his shares to the Cosulich brothers, who were also running a shipping company, operating a total of 14 ships. Those were incorporated into Austro-Americana, and the company henceforth renamed to Vereinigte österreichische Schiffahrtsgesellschaften der Austro- Americana und der Gebrüder Cosulich in 1903. The company now operated a total of 19 vessels. In 1904, Austro-Americana decided to begin offering passenger service to the United States in order to get a share of the increasingly lucrative emigrant market, now competing with big players such as Cunard, Hamburg-America Line, or the North German Lloyd.

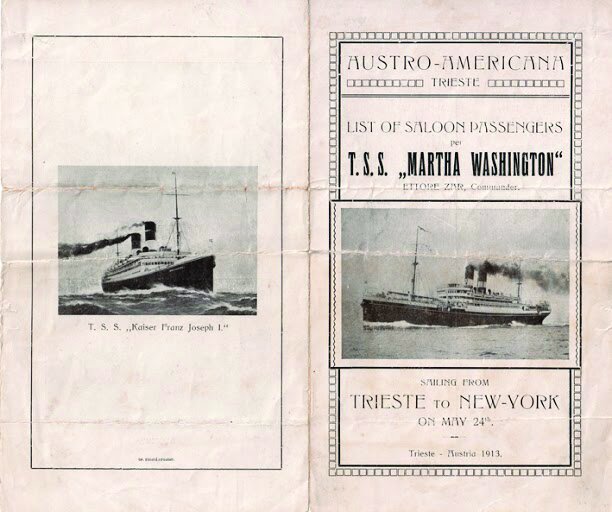

Postcard advertising the Kaiser Franz Josef I

At the same time, Cunard had already reached an agreement with the Hungarian government to provide service for those emigrants. Austro-Americana’s decision to offer passenger service can also be viewed as a reaction to this deal; the initial concern revolved around fears of a possible loss of freight service to Cunard as a side-effect. Thus, Austro-Americana’s first “Emigrant Service,” the Gerty, left Trieste for New York City on June 9, 1904 with 316 passengers on board and stops in Messina, Naples, and Palermo along the way. It has to be noted that, in order to keep up with the before mentioned competition, Austro-Americana did receive government subsidies.

What followed was a massive expansion: by 1912, freight volume had quadrupled and the number of passengers increased from 4,224 per year in 1904 to 10,134 in 1912. Austro-Americana meanwhile had also acquired the rights to transport Italian passengers from Naples and Palermo. Passenger service to America was in such demand that in 1905 the company erected dedicated housing for emigrants waiting for passage in its home port of Trieste, and in 1907 the company began offering service to South America as well. Austro-Americana operated a total of 28 ships that are recorded by the Ellis Island Foundation with their passenger manifestos. Its largest liner, the Kaiser Franz Josef I, was completed in 1912 and provided service to destinations in South America, as well as to New York City.

She had a capacity of 1905 passengers (125 in first class, 550 in second class, and 1230 in third class) and would sail under this name until 1919. While first class passengers were able to travel in great comfort in luxuriously appointed cabins and salons, one can assume that conditions for the more than thousands of men and women in third class were considerably less ritzy. In 1913, the ship had a rather uncomfortable run-in with a whale while en route to the United States, as The New York Times reported:

“The Austro-American liner Kaiser Franz Josef came into port yesterday with a large number of passengers, much cargo, and a story of a whale of great proportions which tried to butt the bottom out of the big liner, and died in the attempt.

The Kaiser Franz Josef was shaken to such an extent that the skipper, all of his junior officers, half of the crew, and scores of the passengers rushed on deck in apprehension. Not until the dead body of the giant mammal was seen floating away to windward did the skipper and his men know what had been under them.”

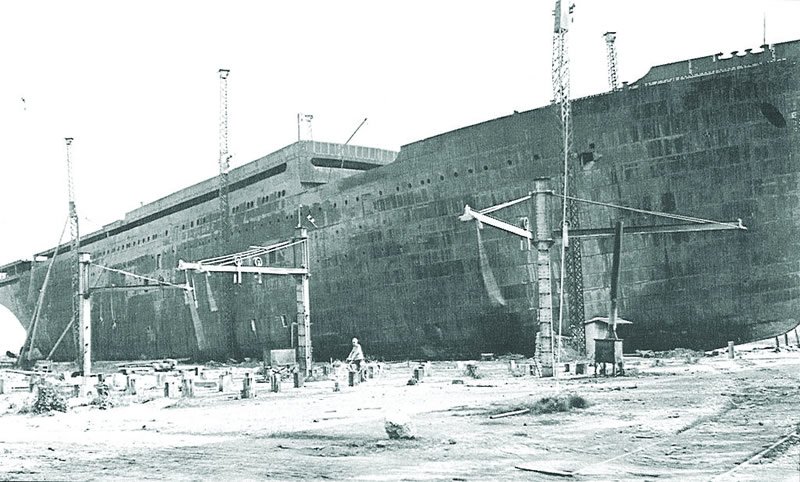

It seems noteworthy that some estimates place the location of this incident approximately over the sinking site of the Titanic, who was lost in 1912. Construction of an even bigger liner for Austro-Americana, the Kaiserin Elisabeth, was never completed due to complications resulting from World War I; she would have been the largest Austrian ship ever built.

Austro-Americana continued to operate successfully; in 1913, before the outbreak of World War I, the company transported 95% of goods between Austria-Hungary and South America. The outbreak of World War I marked the looming end for Austro-Americana in its original form: ships were either impounded or shot at by enemy nations or were put into service for the Austrian Navy.

Constriction of the Kaiserin Elisabeth

After the war, in 1918, only ten ships remained, and since the home port of Trieste came under Italian control, the company was assumed by the Cosulich family and operated as Cosulich Line from this point forward and service to the Americas was eventually resumed. The Kaiser Franz Josef I, which was renamed to Presidente Wilson in 1919 continued her service, and on May 5, 1919, she sailed from Genova to New York again, mostly carrying U.S. soldiers returning home. She was later transferred to Lloyd Triestino in 1930, when she was renamed Gange, and in 1936, she became the property of Adriatica Line and was again renamed to Marco Polo. The Kaiser Franz Josef‘s service ultimately ended when she was scuttled by the German Wehrmacht on May 12, 1944 in La Spezia. In 1949/50 she was re-floated and scrapped.

The era of the jet airplane eventually spelled doom for the great ocean liners, but many aspects of the era can still be found today. The name of Austro-Americana’s co-founder, Gottfried Schenker, today lives on in Schenker AG, a leading shipping and logistics company and subsidiary of Deutsche Bahn AG. The Cunard Line today is owned by Carnival Corporation. After the company had to stop regular service in 1970, it focused on the cruise business. In 2004, however, Cunard began operation of the Queen Mary 2, a proper ocean liner and the company’s first newly constructed ship in 28 years, between New York and Southampton.