Resilient: The Transatlantic Economy in 2022

By Daniel Hamilton and Joseph P. Quinlan

Russia’s further invasion of Ukraine has thrust the world into a dangerous and volatile era. Whatever the ultimate outcome of Putin’s war, the immediate consequences for Ukrainians are horrific, in terms of lives lost, cities destroyed, and families uprooted. The implications for Russia, and for Europe more broadly, are profound, although still uncertain. What is certain: Putin has succeeded in uniting the transatlantic community in ways unknown since Europeans and Americans closed ranks in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States.

North America and Europe are doing what they can to support Ukraine without stumbling into direct military confrontation with Russia. The response has been tough and decisive. North America, the United Kingdom, and EU members, joined by a raft of additional countries such as Japan and Switzerland, have unleashed a barrage of sanctions against Russia. Similar sanctions have been imposed on Belarus.

The impact on the Russian economy has been severe. And while Western leaders have sought to limit the economic blowback on their own economies, Putin’s war has exacerbated inflationary pressures and congested supply chain challenges that were already bedeviling the transatlantic economy. The energy sector and flows of other commodities are particularly affected, with attendant price spikes.

Despite these challenges, what Putin’s war has uncovered is the impressive strength and resiliency of the transatlantic economy. The North American and European economies will be far better able to withstand the pain of sanctions than will the Russian economy. Apart from Europe’s significant dependence on Russian energy, Western economies overall have limited exposure to the Russian economy and are relatively insulated from the impact of Russia’s growing economic isolation. U.S.-Russia trade is negligible; Russia accounts for roughly 0.55% of total U.S. trade in goods and services. And while the European Union is Russia’s largest trading partner, accounting for 37% of Russia’s global trade in 2020, Russia represents only around 5% of the EU’s trade with the world. Russia is a relatively minor player in the global economy, accounting for just 1.7% of the world’s total output—a figure that has surely already shrunk since Putin initiated his latest invasion.

Moreover, the two sides of the North Atlantic enter 2022 in a strong position. In a remarkable demonstration of resiliency and dynamism, the key drivers of the transatlantic economy—investment, income, and trade—staged a robust rebound in 2021. Indeed, 2021 was record breaking on many fronts. Transatlantic trade in goods reached an all-time high of $1.1 trillion in 2021. U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to Europe surged to an all-time high of $253 billion; U.S. foreign affiliate income earned in Europe topped $300 billion for the first time; European affiliates in the United States earned a record-breaking $162 billion; and European FDI flows into the United States surged to the highest levels since 2017, hitting $235 billion.

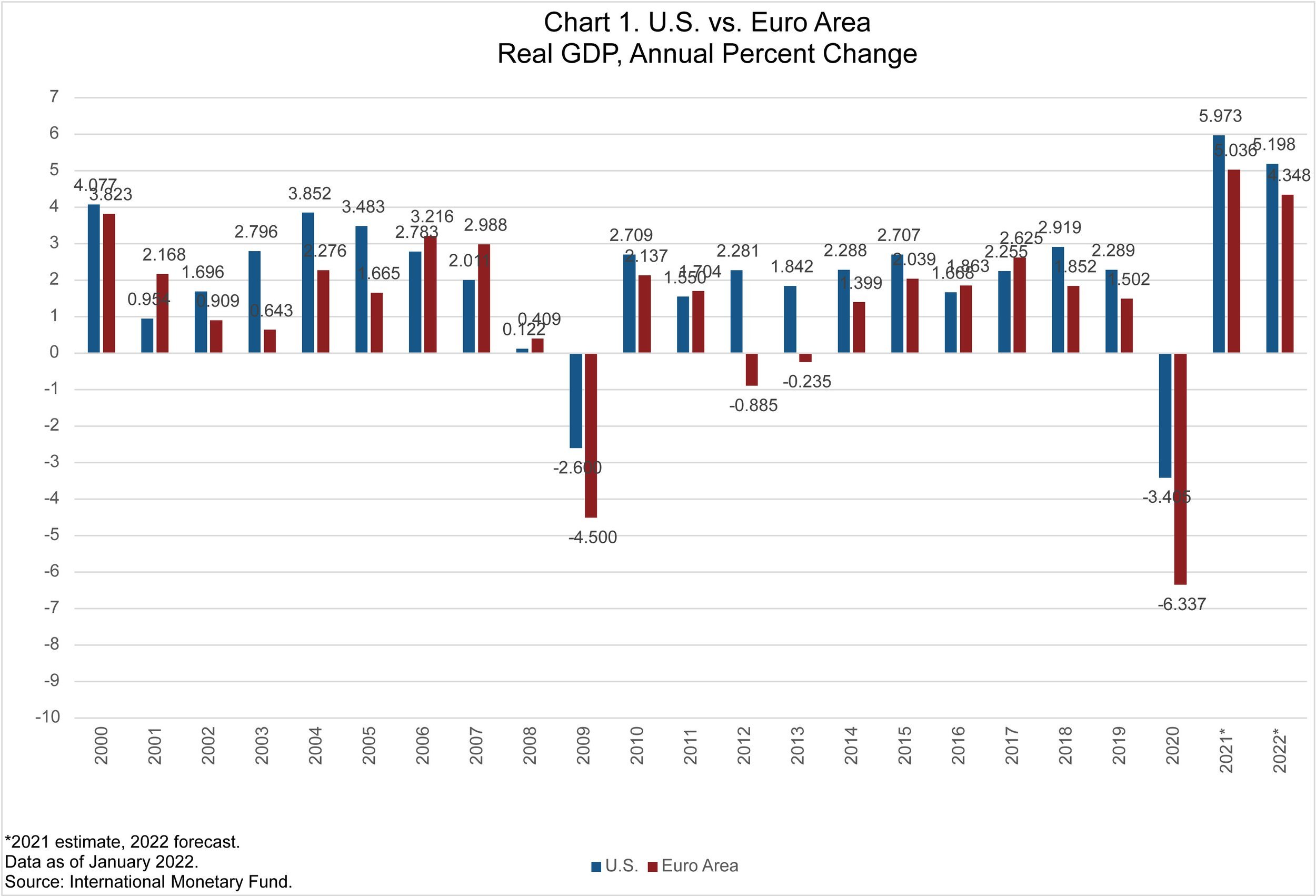

These figures are emblematic of a world economy that recovered much faster from the COVID-19 pandemic than most expected. Owing to rising global vaccination rates, notably in the developed markets of the United States and Europe, and to uber-monetary and fiscal support, the global economy staged an impressive rebound from the dark days of March 2020, when COVID-19 brought things to a standstill. Global output in 2020 contracted by a stunning 3.4%, one of the severest downturns on record. U.S. output dropped by the same amount, while economic output in the eurozone plunged 6.4%.

Last year, however, as the world emerged from the pandemic-related lockdowns of 2020, global growth surged, fueled by soaring consumption and investment, and backstopped by generous levels of public sector spending. Global output in 2021 rose 5.6%, one of the strongest economic rebounds in decades. France’s economy expanded by 7%, the highest for half a century and the best in the G7 group of big, industrial nations, followed closely by the United Kingdom at 6.9%. The U.S. economy grew by 6%, with real GDP reaching pre-pandemic levels in the second quarter of 2021. The euro area posted growth of 5% in 2021, and many European economies are on their way to reaching pre-pandemic levels of output.

Both the United States and Europe are poised for solid economic growth in 2022, with the disruptive effects of the pandemic likely to fade, the impact of Russia’s isolation largely manageable, and as the spillover effects of easy monetary and fiscal policies help to grease economic activity. The combined U.S. fiscal and monetary response—over $12 trillion in 2020-2021—was more than half of U.S. GDP, representing one of largest government spending surges in U.S. history. European policy makers also stepped up in a big way, with eurozone and UK governments introducing roughly $8 trillion in fiscal and monetary stimulus since the beginning of the pandemic.

As policy tailwinds fade in 2022, the baton of growth is being passed to consumers and companies. The outlook for U.S. consumer spending is one of the strongest in years, with full employment, rising wages, and rising home and stock values helping to drive increased spending levels, notably among high-income households. The downside: real wages in the United States and Europe are falling due to the effects of accelerating inflation, hurting low-income families the most. This dampening effect is expected to be offset by rising pent-up spending among various cohorts on both sides of the Atlantic.

Transatlantic personal consumption accounted for roughly half of global consumption in 2020, versus India and China’s combined share of 15%. This fact underscores the attractiveness of the transatlantic economy and reinforces a point we have long made: notwithstanding rising consumer expenditures in China, the United States and Europe still control the commanding heights of global consumption. Consumption is dependent on per-capita income, and based on this metric, the average transatlantic consumer is far wealthier than their counterparts in Asia’s twin giants.

In terms of corporate spending, U.S. firms were sitting atop some $7 trillion in free cash flow at the end of 2021, thanks to record corporate profits and the low cost of credit. Firms on both sides of the pond are flush with cash, which portends more transatlantic mergers and acquisitions (M&A), more hiring, even faster wage growth, and more bilateral investment in 2022.

Transatlantic goods trade soared in 2021, with both U.S. goods exports to Europe (estimated $382 billion) and U.S. goods imports from Europe (estimated $667 billion) hitting record highs. This discrepancy also led to an all-time merchandise trade deficit of $285 billion. That said, there is more to transatlantic trade than goods. Commercial transactions are far more balanced if one includes services trade, digitally-enabled commerce, and investment flows. For instance, we estimate that U.S. foreign affiliate sales in Europe totaled $3.1 trillion—roughly half of the global total and 45% larger than U.S. affiliate sales in all of Asia—in 2019, the last year of available data. Affiliate sales are also the primary means by which European firms deliver goods and services to customers in the United States. In 2020, for instance, we estimate that majority-owned European affiliate sales in the United States ($2.6 trillion) were more than triple U.S. imports from Europe.

Taken together, U.S. and European goods exports to the world (excluding intra-EU trade) accounted for roughly 26% of global goods exports in 2020, the last year of complete data; combined goods imports represented around one-third of the world total. Meanwhile, the United States and Europe together accounted for roughly 64% of global inward stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) and 65% of outward stock of FDI. Each partner has built up the great majority of that stock in the other economy. Mutual investment in the North Atlantic space is very large, dwarfs trade and has become essential to U.S. and European jobs and prosperity. Over 70% of global M&A deals are between the United States and Europe.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the largest commercial artery in the world stretches across the Atlantic. Total transatlantic foreign affiliate sales were estimated at $5.7 trillion in 2020, easily ranking as the top artery in the world on account of the thick investment ties between the two parties.

The transatlantic theatre is the fulcrum of global digital connectivity. Transatlantic flows of data continue to be the fastest and largest in the world, accounting for over one-half of Europe’s global data flows and about half of U.S. flows. U.S. exports of ICT-enabled services to Europe of $247 billion were about 2.7 times greater than U.S. digitally-enabled services exports to Latin America, and roughly double U.S. digitally-enabled services exports to the entire Asia-Pacific region. The United States, in turn, accounted for 22% of the EU27’s ICT-enabled services exports to non-EU countries, and 34% of EU digitally-enabled services imports from non-EU countries in 2020. The EU’s digital trade with one country—the United States—is only slightly less than its entire digital trade with all of Asia and Oceania.

Even more important than trade, however, is the delivery of digital services by U.S. and European foreign affiliates. ICT-enabled services supplied by U.S. affiliates in Europe were almost double U.S. ICT-enabled exports to Europe, and ICT-enabled services supplied by European affiliates in the United States were double European ICT-enabled exports to the United States.

Transatlantic energy connections are also growing in importance, as the United States becomes the world’s largest supplier of liquefied natural gas (LNG), and as U.S. and European companies lead the transition to competitive clean technologies. The U.S. has become Europe’s largest LNG supplier, accounting in 2021 for 26% of all LNG imported by EU member countries and the UK. In January and February 2022, the U.S. supplied more than half of all LNG imports into Europe, shipping more to Europe than ever before. Europe accounted for about 75% of all U.S. LNG exports, far outpacing exports to Asia. Moreover, for the first time ever, U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas to Europe exceeded Russia’s overall natural gas pipeline deliveries.

European companies are the top source of FDI in the U.S. energy sector. Moreover, U.S. companies in Europe have become a driving force for Europe’s green revolution, accounting for more than half of the long-term renewable energy purchase agreements in Europe since 2007. U.S. companies account for three of the top four purchasers of solar and wind capacity, and five of the top ten purchasers of renewable energies, in Europe. Europe and the U.S. made up 67% of all green bonds issued in 2020, and 68% of the total $1.7 trillion in green, social, and sustainable debt issuance.

In addition to the above, the transatlantic innovation economy is a repository of technological advancement. Bilateral U.S.-EU flows in research and development (R&D) are the most intense between any two international partners. U.S. affiliates spent $32.5 billion on research and development in Europe in 2019, the last year of available data. Europe accounted for roughly 56% of total U.S. global R&D expenditures. European companies spent roughly the same—$33.5 billion on R&D in the United States, and accounted for two-thirds of all such spending flowing into the United States.

All told, the $6.3 trillion transatlantic economy remains the largest and wealthiest market in the world, employing 14-16 million workers on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite stories about companies decamping from high-cost countries to low-cost labor markets, Europe is by far the most important source of “onshored” jobs in America, and the United States is by far the most important source of “onshored” jobs in Europe.

In recent years, the full potential of the transatlantic economy was challenged by multiple policy disputes. Here too, the clouds seem to part and the skies brightened in 2021. While a number of irritants persist, the Biden administration and EU leaders used 2021 to address lingering problems and set the stage for a relationship better positioned to deal with a turbulent global economy. The two sides created a Trade and Technology Council to align their approaches on a host of issues, ranging from supply chain resilience, promotion of clean technologies and export controls to standards for emerging technologies, data governance challenges, and misuse of technology impairing human rights. They postponed niggling trade issues over aircraft subsidies, steel and aluminum tariffs, and pledged to devise new trade arrangements that could better advance low carbon strategies. They joined forces to fight the climate crisis.

This newfound sense of transatlantic unity is an opportunity for the United States and the EU to address lingering irritants in their own relationship. U.S. concerns center on the motivations behind the collapse of the U.S.-EU Privacy Shield governing transfers of personal data, the protectionist impulses behind the Digital Markets Act, industrial strategies intended to promote “European champion” companies, and the EU proposal for a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which could disadvantage non-EU companies. The EU worries about the Biden Administration’s efforts to strengthen “Buy America” rules, its proposals for electric vehicle tax credits, and its decision to postpone but not resolve transatlantic disputes on U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs. Each party’s efforts to subsidize its semiconductor sector and other digital industries could lead to subsidy wars that would only benefit China.

Negotiations on a successor agreement to Privacy Shield are particularly fraught. Transatlantic data flows—the lifeblood of the transatlantic economy—remain in legal limbo after the European Court of Justice in summer 2020 invalidated for a second time U.S.-EU arrangements governing the transfer of personal data for commercial purposes. Negotiators are seeking yet another successor agreement, which U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has called “the number one priority.” However, since the Court’s judgment is rooted in differences in law rather than in policy, even a Privacy Shield 2.0 is likely to face legal challenges from within the EU.

These policy differences, while quite real, are now playing out in a context of transatlantic unity rather than division. In 2021 the transatlantic tone changed markedly; in early 2022 the transatlantic partners have joined forces against a common threat. The test they face now is to manage their sanctions effort, and to reduce their reliance on Russia, while limiting the damage to their own economies and building on the impressive strengths of the deeply interconnected transatlantic economy. Despite Putin’s disruptive war, the macroeconomic and policy backdrops for the transatlantic economy are generally quite positive for 2022. Real growth is decelerating but at above-average historical levels. The drivers of growth are shifting from the public sector to the private sector, while employment levels remain strong. Pre-pandemic output levels will be achieved in many economies. Bilateral trade and investment flows are solid. There are bumps on the road to recovery, yet transatlantic partnership rebounded in 2021, is proving itself to be resilient in the face of new challenges, and all indications are that it will forge ahead again in 2022.

Austria’s Stake in Healthy Transatlantic Commerce

Austria is a prime example of the extensive commercial connections that bind the two sides of the North Atlantic. According to our estimates, roughly 120,000 Austrians owe their jobs either to U.S. companies based in Austria or to Austrian exporters to the United States, or their affiliated suppliers and distributors. Austria’s investment stake in the United States has essentially doubled since 2015, totaling $15.7 billion in 2020. The United States also accounted for 21.5% ($11.6 billion) of Austria’s goods exports outside the EU in 2020. California, Georgia, South Carolina, Texas and New Jersey were the top U.S. markets for Austrian goods. Total bilateral trade in services accounts for another $2 billion.

Austria’s stake in healthy transatlantic commerce is even higher if one considers how Austrian companies have become deeply integrated into global value chains, which render a country’s exports essentially the product of many intermediate imports assembled in many other countries. In today’s global economy, a good produced in Austria and exported to the United States might include components from Romania or China, use raw materials from Ukraine or Australia or incorporate services from Turkey or Switzerland. Similarly, many Austrian exports of parts or components to Germany, Italy, or France are then assembled as value-added elements of a final product that is sent to a final customer who is based in America, making the United States a more important commercial partner for Austria than commonly understood. During the pandemic, deep transatlantic economic integration helped U.S. and European firms weather the storm, with firms on both sides of the pond better able to access the markets and resources of the broader transatlantic economy to their advantage. The partnership, even in the face of significant challenges, will forge ahead again in 2022.

Daniel S. Hamilton is Senior non-resident Fellow at the Brookings Institution, a faculty member at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, and President of the Transatlantic Leadership Network.

Joseph P. Quinlan is Senior Fellow at the Transatlantic Leadership Network, with extensive experience in the U.S. corporate sector.

Together they are the authors of The Transatlantic Economy 2022 (Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University, 2022)

For more information, visit https://transatlanticrelations.org